When Your Productivity System Breaks You

Human Be(com)ing • or, Trust Over Tools: Accepting Limitation as Invitation

Human Be(com)ing explores how to desire better, decide wisely, and act differently in an often overwhelming and bewildering age.

Greetings, exhausted elves!

Let’s jump into it, shall we?

The moment I knew something had to change came this past summer. I found myself feeding my weekly reflections into an LLM because I couldn’t stand the thought of making sense of what I’d collected for a monthly review.

I smacked myself and asked: What is this for?

If reflection is helpful practice, I don’t need AI to summarize it. And if I need AI to make sense of my own thoughts, something has gone very wrong.

Looking back over 2024 and into 2025, I’ve been sitting with a question: What if modern productivity culture encourages us to optimize our way out of our human limitations rather than learn to live well within them? This creates exhaustion, measuring our worth by how effectively we perform, not by who we’re becoming. It encourages us to treat our constraints as failures to fix, not features to work with.

But what if limitations aren’t bugs to fix but invitations? What if the very things I’ve been trying to engineer my way out of are actually invitations to trust—in God, in my own wisdom, in the relationships and communities around me?

This week I want to explore systems design as a formative practice—learning to make choices that honor who we actually are instead of who we think we “should be.” By offering patient, non-judgmental attention to our design, we can cultivate rhythms that expect limitation rather than try to transcend it. We can appreciate the slow formation of practicing over producing, becoming over achieving.

So here’s a little story about what I learned when my oh-so-carefully engineered system finally broke me, and what I’m learning about trust these days.

If you’re sick and tired of holiday eggnog, iced sugar cookies, and angry elves at this point,1 and ready to curl up in your jim-jams and ignore the world… Perfect. Because that sense of exhaustion—the kind that comes from running hard and hitting your limits—is exactly where this story begins.2

How I Got Here

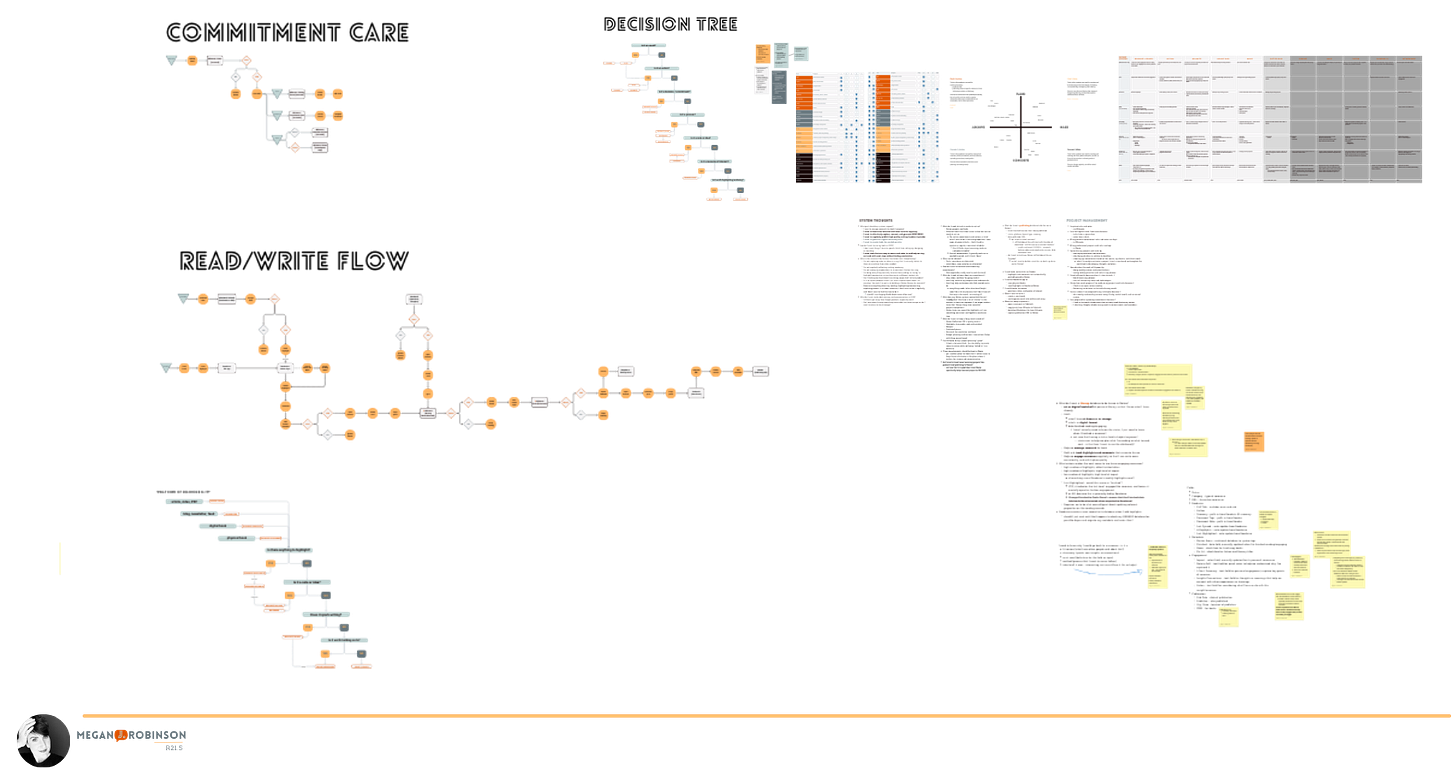

At the end of 2024, I wrote an essay about how systems and tools help us become ourselves. I shared my elaborate setup—the process maps, the decision trees, the borrowed and cobbled-together frameworks. It was thorough. Comprehensive. Maybe even impressive.

Friends, that was…a lot. A whole lot of a lot.

To understand how I ended up with multiple time-tracking systems and an automation pipeline for my highlights, let me rewind to 2019.

I’d just finished a master’s degree while working full-time. Beyond the usual post-goal slump, I felt genuinely at loose ends. The anticipated abundance of opportunities hadn’t materialized—or at least, that’s how it felt. I had a lifetime of ideas and dreams that felt consistently unfulfilled, and a growing sense that while I wasn’t incapable, I also wasn’t effective at the things that mattered most to me.

Then I discovered Notion.

When I realized its potential for custom-building tools that worked for me—not templates designed for someone else’s brain—I went a little nuts. My friends and family can tell you about my evangelistic fervor.3 I spent hours binge-watching YouTube videos, duplicating templates, reverse-engineering other people’s setups, learning to build my own from scratch. I loved it.

When I couldn’t get the results I wanted, I learned to “ask better questions” by figuring out which properties, relationships, and processes would actually get me where I wanted to go. I externalized my emotions, physical health, and work patterns in ways I’d never been able to before. I learned to see systems—in the world and in myself—in completely new ways.

Most importantly: I made progress on ideas and goals that had been stuck for years.

I wouldn’t trade this learning for anything. Those hours of tinkering taught me legitimate skills. The custom tools solved real problems. I covered real ground.

But the systems that helped me break through were also creating a pattern I didn’t recognize. Each success reinforced the belief that better systems would solve whatever came next. Each new tool promised to fill the gap between where I was and where I wanted to be.

The problem wasn’t the tools themselves. The problem was that I’d gone from “this helps me work with my limitations” to “if I just had the right system, I wouldn’t have limitations.” I went from working with myself to trying to engineer my way out of myself.

When Good Systems Go Bad

When I look back at those system maps now, I cringe. The hours spent process-mapping everything. The endless notes trying to anticipate future scenarios. The tools for tracking tools that captured highlights from tools. At one point I tracked my time in three places. I can’t even tell you why.

My setup for managing what I read and learned had become especially elaborate. I was using five different apps just to save and organize articles, highlights, and ideas.4 One tool fed another through automations. Every tool felt necessary. Vital. A bulwark against my scattered brain and an undefined future.

I’d become a museum curator of other people’s ideas instead of generating my own insights. I highlighted every resonant sentence, feverishly organized my collections, told myself I’d use them “later.” I saved cool things “just in case.”

Later never came. And “just in case” felt like a hiker’s backpack growing heavier with every mile.

I used to have my own insights. I wrote a thesis with basically a pen, a notebook, and MS Word. Where had that person gone?

None of these tools were necessary to do the work I actually wanted to do. But somehow I’d become convinced that simple and easy were no longer sufficient. I kept feeling like there was a problem in my system that I was failing to solve. If I could just find the One Rin…Tool5 to bring everything together, I’d finally be able to think clearly, create freely, become who I was meant to be.

I kept trying to fix a technical problem (which tool?) when the real challenge was adaptive. Ronald Heifetz writes about this, observing how technical challenges have clear solutions that don’t require much change from us. Adaptive challenges, on the other hand, require “changes in values, beliefs, roles, relationships, and approaches to work.”

The real problem wasn’t my tools. It was that I’d stopped trusting my own capacity to know, to remember, to discern what mattered. I was outsourcing trust to my systems instead of learning to trust the skills and insights I already had.

Uff-da, as a friend would say.

The Pattern Behind the System

Over the last few months, I’ve been sitting with a question: How are my limitations an invitation to trust—in God, in my own wisdom, in others? How might my limitations actually be the starting point for doing the work I want to do?

As someone with a reputation for competence, I’ve had a hard time recognizing my stranglehold on control. When you can perform to expectations, it’s painful to realize you’ve deluded yourself into thinking you’ve got it all handled.

Then this past summer, I had an insight about my Enneagram type that made everything click into terrible, clarifying sense.

For those unfamiliar: the Enneagram describes nine personality patterns, each with distinct motivations and fears. The Type 4—often called “The Individualist”—is driven by the desire to be unique and authentic, but struggles with a core wound of feeling fundamentally flawed or deficient.6

This :::waves hands::: was a classic Enneagram 47 pattern—perfecting my process while avoiding the vulnerable work of actual output. For a 4, sophisticated systems can become part of one’s unique identity. Not just “I’m a writer,” but “I’m someone with this deep, nuanced approach to knowledge that others don’t understand and couldn’t possibly replicate.” The elaborate setup becomes a way of saying, “My mind works in complex, interesting ways that require special tools.”

My productivity system obsession was a sophisticated form of creative avoidance. Building systems provided the identity of “someone with interesting creative processes” without the vulnerability of actually sharing creative work. I could perfect my process while avoiding output. Ouch.

The 4’s core wound of feeling fundamentally flawed creates paralysis around creative expression. If the work isn’t ready (and when is it ever ready?), if it might be ordinary, if people might not care what I have to say… Better to tinker with the system than risk finding out.

That’s why the identity threat of simplification cut deep: going back to notebooks and letting ideas go felt like becoming ordinary. Just another person who writes without special methodology. For a 4, this can feel a bit like losing one’s self.

But truly… My authentic voice comes from my actual thinking, not from information management. All of these fantastic systems were covering up my natural creative uniqueness with borrowed “productivity culture” identity.

And underneath all of it? A fundamental insight about trust. I’d been conflating trust in my own experience and wisdom with trust in my ability to control everything.

Building elaborate systems felt like trusting myself—look how capable I am! But I was actually trusting my ability to engineer control, not my capacity to navigate uncertainty. Not my capacity to trust that God has already prepared me for what I needed to do.

Permission to Let Go

This realization about control and trust opened something in me, or maybe it just made space to hear what was already there.

Over the summer, I encountered Joan Westenberg’s essay “I Deleted My Second Brain.” Westenberg writes about throwing everything into the trash and living in the sudden silence that followed.

I was enamored.

My archive, the tools, the processes—they had become a Sisyphean rock I’d been pushing uphill for years, convinced that just a little more optimization would get me to the top. Could I just…let go? Stop pushing? Be done with it?

It felt like permission. It felt like relief. It felt like the start of something real.

Maria Bowler writes: “When you don’t trust the tools sitting in your belt, you’ll scramble for more and different. It keeps you consuming illusions of certainty, and very busy.”8

That was it exactly. I didn’t trust my own knowing—my capacity to see patterns and make sense without capturing everything first. So I kept looking for more tools, more systems, more certainty. More insurance against an uncertain future I couldn’t control anyway.

But what if I could trust differently? What if instead of trusting my systems to save me from limitation, I could trust that my limitations were themselves a gift? An invitation to depend on God, to receive from others, to work with myself rather than constantly trying to “make up” what I think is lacking?

The Experiments

I started simple:

Unsubscribed from 60+ sources

Deleted my reading app archives

Deleted 90% of my resource collections

Disconnected automatic highlight syncing

Stopped saving everything indiscriminately

It felt strange. The sudden silence was disorienting. But also—relieving. Like I’d been telling myself “you can’t trust anything if you haven’t tracked it,” and now I was testing whether that was actually true.

Then I tried something wild: I loaded a year’s worth of reviews, experiments, and reflections into an LLM alongside my stated values and principles. I asked it to show me what patterns it saw.

I literally read myself telling me about myself.9 The same insights, the same struggles, the same wisdom appearing over and over. Not because I’d captured the right highlights, but because I’d been paying attention all along.

I already knew what I needed to know. I just hadn’t…trusted it.

What Actually Changed

I’m not going to pretend I’ve “made it.” This self-trust thing feels weird. But here’s what shifted:

I went from five apps for reading and notes to three simple tools. From elaborate process maps to a single weekly review framework. From tracking everything to trusting I’d remember what mattered.

The specifics matter less than the principle: I stopped asking “What tool will fix this?” and started asking “What am I actually trying to do?”

My tools now fit in one sentence: Apple’s built-in apps for tasks and calendar, a notebook for reviews, and one writing space. That’s it.

My rhythms honor how my energy actually moves instead of how I wish it moved: structured work Monday through Thursday, transition time Friday and Saturday, creative flow on Sundays.

My reflection practices are stupid simple: a weekly Plus-Minus-Next review on Friday mornings, a monthly reflection using personal prompts, and trusting that pen and paper are enough.

The structure isn’t fancy. But it honors a truth I’d been avoiding: I have limits, and those limits aren’t problems to solve. They’re the shape of my particular life, and working within them rather than against them is itself a spiritual practice.

You’re probably thinking, “Okay, but how does this actually work? What does this look like day-to-day? How does this help me figure out my own version?”

Next week, I’m popping the hood so you can see everything. I’ll show you the actual tools, the specific rhythms, the questions I ask to keep myself honest. Not because you should copy my setup—you absolutely shouldn’t—but because seeing how someone else works with their limitations might help you work with yours.

We’ll look at how to build a system that anticipates your limitations instead of trying to ignore them. How to know when you’re solving real problems versus avoiding uncomfortable work. How to find “good enough” for your actual life, not the life you think you should have.

If you’ve been cycling through systems hoping the next one will finally fix you, or if you’re drowning in tools that promised to help, but now just add weight—next week is for you.

What I’m Still Learning

I still struggle with trusting the transition from capture to creative output. My body still signals stress through recurring pain and fatigue that I’d rather manage around than honor. I still catch myself wanting to build a new system when the real issue is doing the uncomfortable work with the system I have.

But I’m learning to ask different questions:

What if my constant system-cycling was actually giving sparkler-energy, not bottle rocket-energy?

What if sophistication in systems was preventing sophistication in thought?

What if accepting my limitations is actually the path to doing my best work, not the obstacle preventing it?

What would it mean to find my creative identity in the work itself rather than the system?

“How much more of you could be present if you could trust that your knowing would unfold exactly at the right time? How much more would you show up if, instead of needing to have mastered all the moves for every unfamiliar or challenging circumstance, you knew that you were already that which is needed in the moment?” -Maria Bowler

Moving Forward

I’ll be honest—over the last couple of years both my family and I have faced a lot of changes. Changes that feel like loss, that I’m only just now realizing I haven’t fully processed or grieved. In some ways, I think my efforts at system “optimization” masked my attempts to avoid being present to these changes. “If I can just fix and make this thing perfect, then that’ll make everything else fine.”

But part of growing and learning is accepting that these changes will unfold in your life, and allowing them to be the messy, hard, sad, transformative things that they are. Sometimes I wonder if I’ll ever fully learn this, or if I’ll always be surprised when life asks me to trust again. Life provides a lot of opportunities for practice.

So in that spirit, I’m committing to three practices for the next season:

Practice self-compassion. My body signals through pain and exhaustion when I’m pushing too hard. Health deserves the same attention I give to business development. Trust means listening to these signals, not managing around them.

Expect God to do more than I can imagine. My biggest breakthrough came after I released control. Setting boundaries, then letting go of outcomes. Trusting that what I need will be there when I need it.

Simplify to encourage creative truth. System-cycling is procrastination disguised as optimization. I’m committing to my current setup for six months minimum—no more system changes. Trust means staying put long enough to actually see what works.

The discipline here, for me, is learning to accept “good enough” as actually good. Not settling for mediocrity, but recognizing that human-scale lives require human-scale solutions. That working within our design rather than trying to transcend it is itself an opportunity for grace.

Systems and tools will only replicate our underlying anxiety, fear, or dysfunction. The question isn’t “Which tool?” but “What am I trying to avoid by constantly switching tools?” No amount of tool hopping will ever address the deeper question of whether we trust how we’re designed.

Maybe you’re facing something similar—not the exact same systems, but the same pattern of optimization-as-avoidance, of treating your limitations as problems instead of starting points. The same question about whether you can trust your own wisdom, your own design, the way God has already prepared you.

What would change if you trusted how you’re already designed?

Take a look at how you responded to last week’s SloDo. Has anything from this essay illuminated, transformed, or otherwise changed about your response?

If you found this helpful, and you’re curious about Systems Therapy, learn more here and book a Curiosity Call!

Let’s be hopeful, creative, and wise—together.

Shalom,

What else?

Have a question? Ask me anything.

A Note on AI

I use LLMs at the END of my writing process, to help me edit the work, zoom out to find patterns I’ve missed, and generate social media posts, title ideas, and other related tasks that make me want to shrivel up in a corner and die. The blood, sweat, and tears are wholly my own.

Use this worksheet to take notes!

Sorry, y’all.

Oh here, just let me expose my still-beating heart to the world.

Cannot recommend this book enough.

So very Inception-like!